CHUTZPAH IN BABYLON

Art historian, scholar and long-time collaborator Patrick Bade comments on the art and meaning behind Verdi’s opera Nabucco

Companion article to Episode 1 of MUSIC IN THE TIMES OF CRISIS

The Yiddish word chutzpah, meaning excessive confidence and ambition, has crossed linguistic barriers and would now be understood by most of the descendants of the peoples of Babel. In modern parlance the term can be used admiringly of someone who is courageous and innovative. In the Hebrew Bible, however, overweening ambition is inevitably punished. Three of the most famous examples concern either the historical or a mythological version of the city of Babylon – indeed the word “Babylonian” itself has become synonymous with excess of one kind or another.

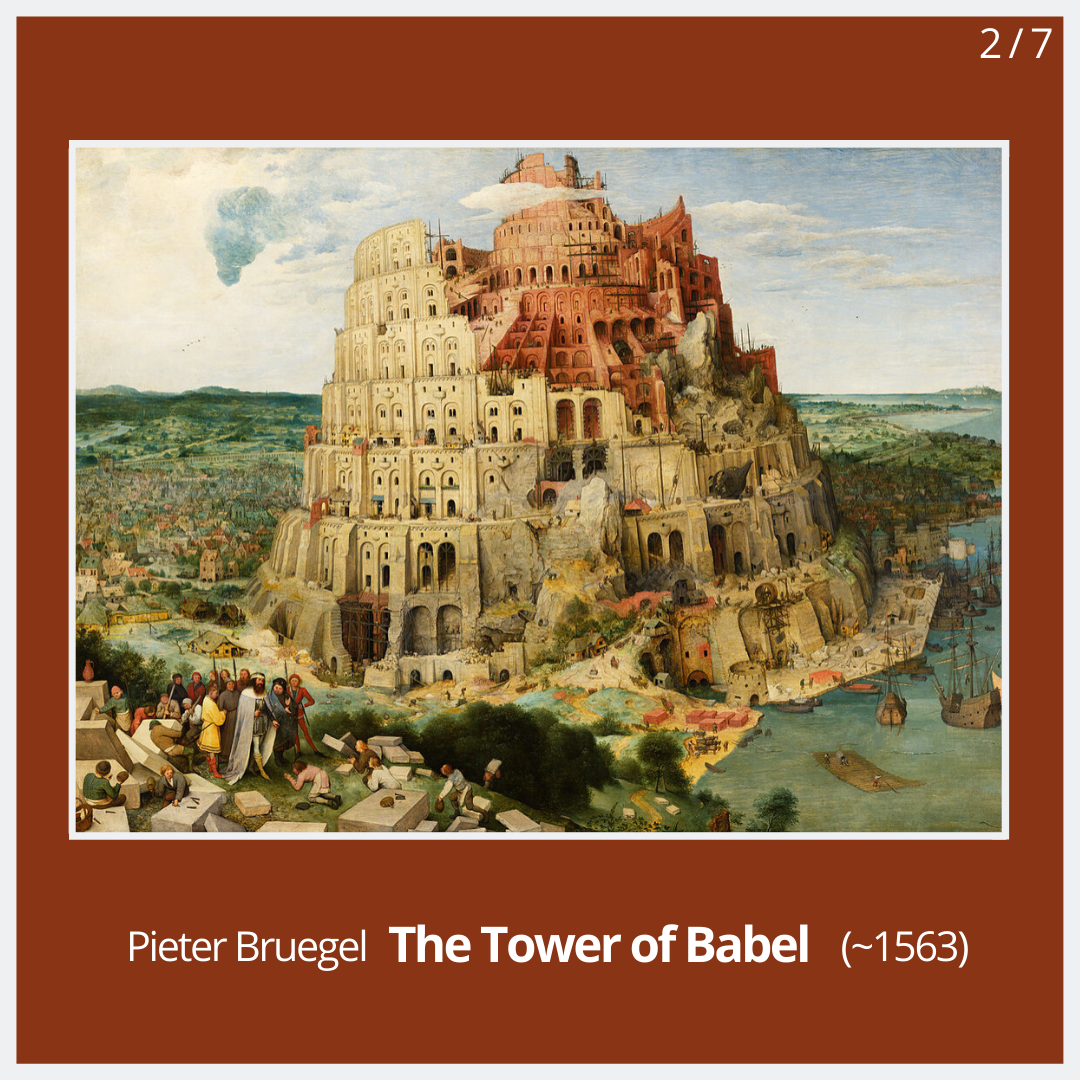

The story of the Tower of Babel is told in Genesis 11:1–9. After the Great Flood, mankind becomes over-confident and the people of Babel decide to build a tower that will reach up into heaven:

And the Lord came down to see the city and the tower which the children of men builded.

And the Lord said, Behold, the people is one, and they have all one language: and this they begin to do: and now nothing will be restrained from them, which they have imagined to do.

Go to, let us go down, and there confound their language, that they may not understand one another’s speech. (Genesis 11: 5–8)

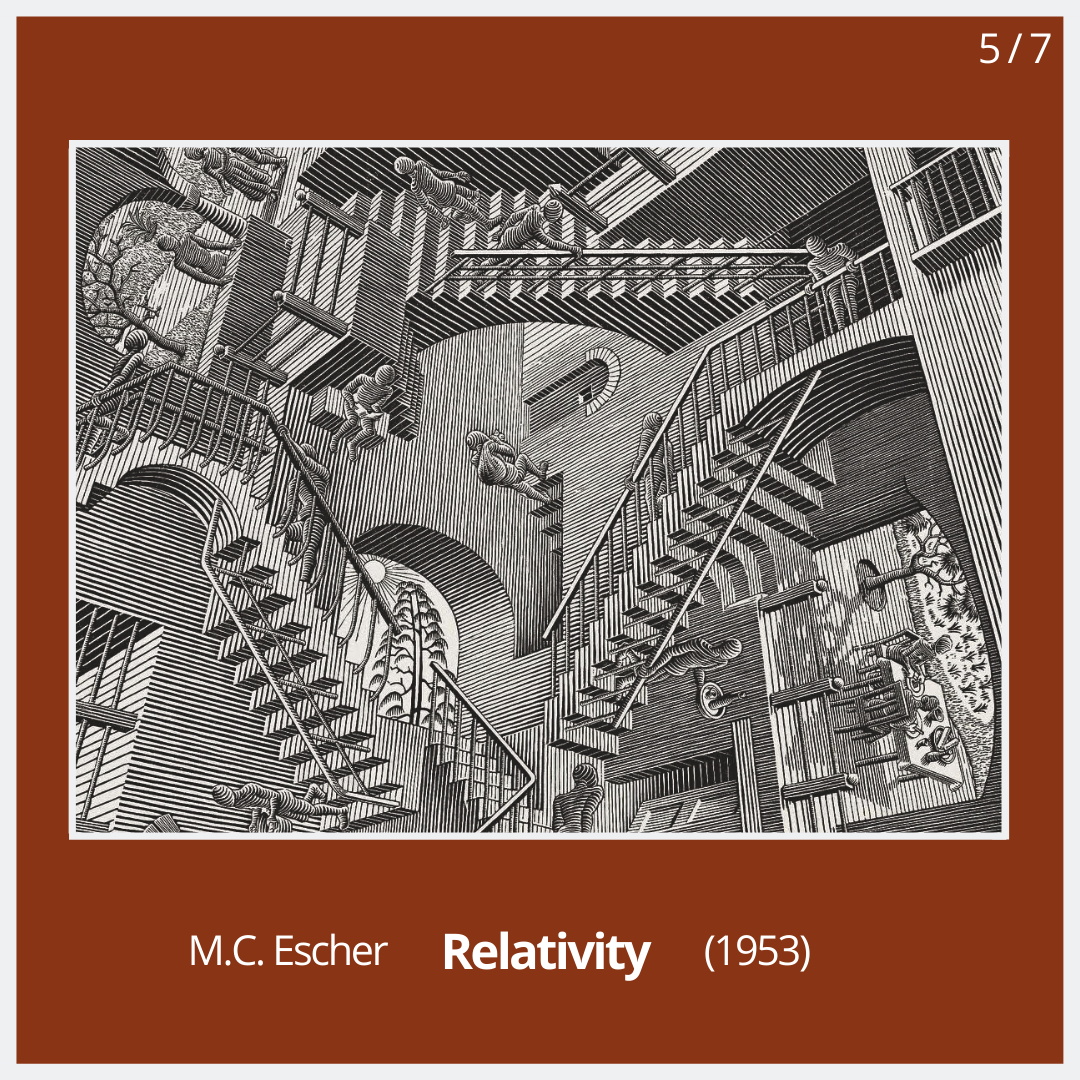

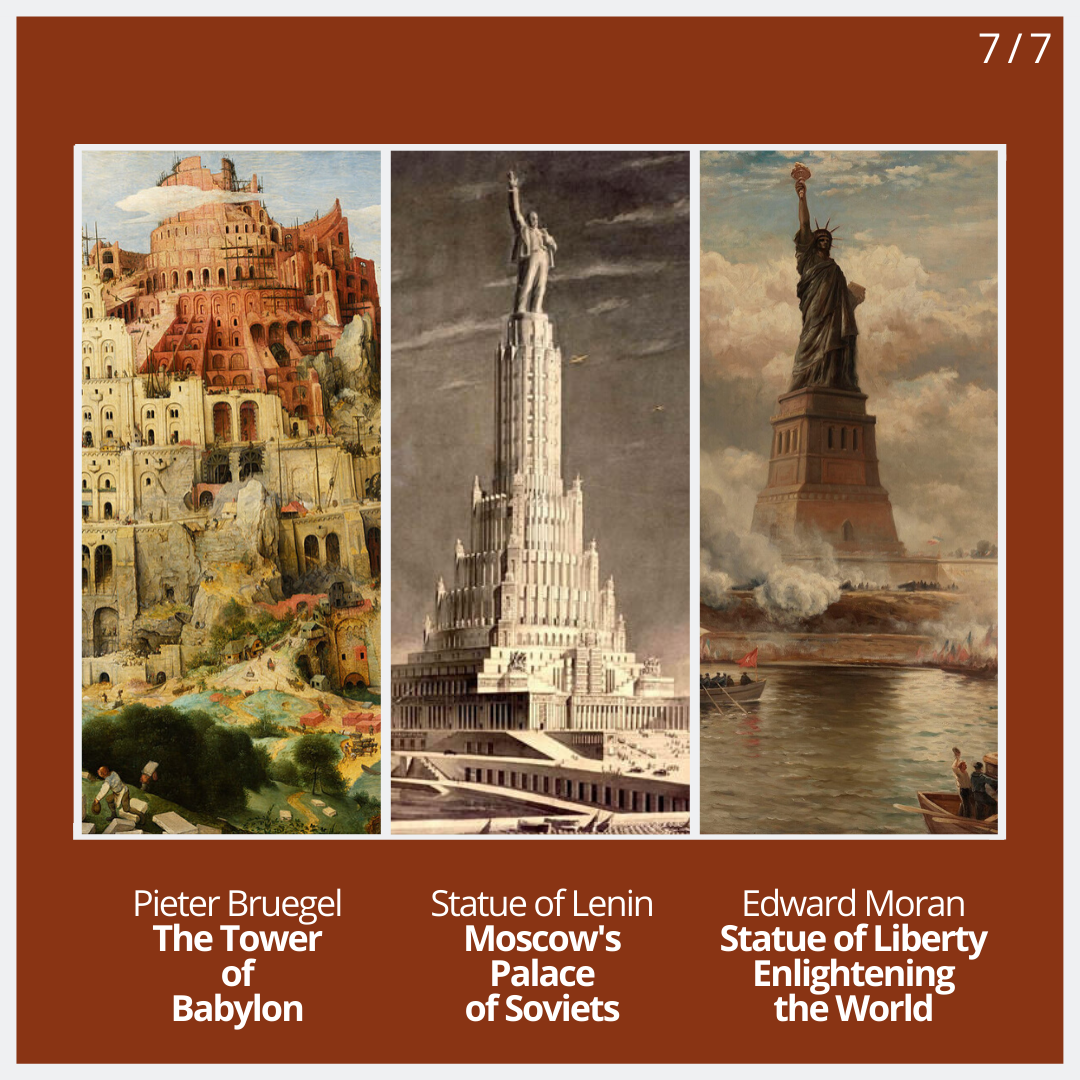

Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s masterpiece The Tower of Babel (Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna), teeming with fascinating detail, is one of the most memorable images in Western art. Numerous copies and variants were made at the time and its influence reached into the twentieth century, as can be seen in the graphic work of the Dutch artist M.C. Escher, the set designs for Fritz Lang’s movie Metropolis and the entries for the 1931 competition for the Palace of the Soviets. The winning design by Boris Iofan, Vladimir Shchuko and Vladimir Gelfreikh for a building intended to be the tallest in the world, suffered a similar fate to that of the original Tower of Babel. Three years into construction, it was abandoned after the Nazi invasion of Russia.

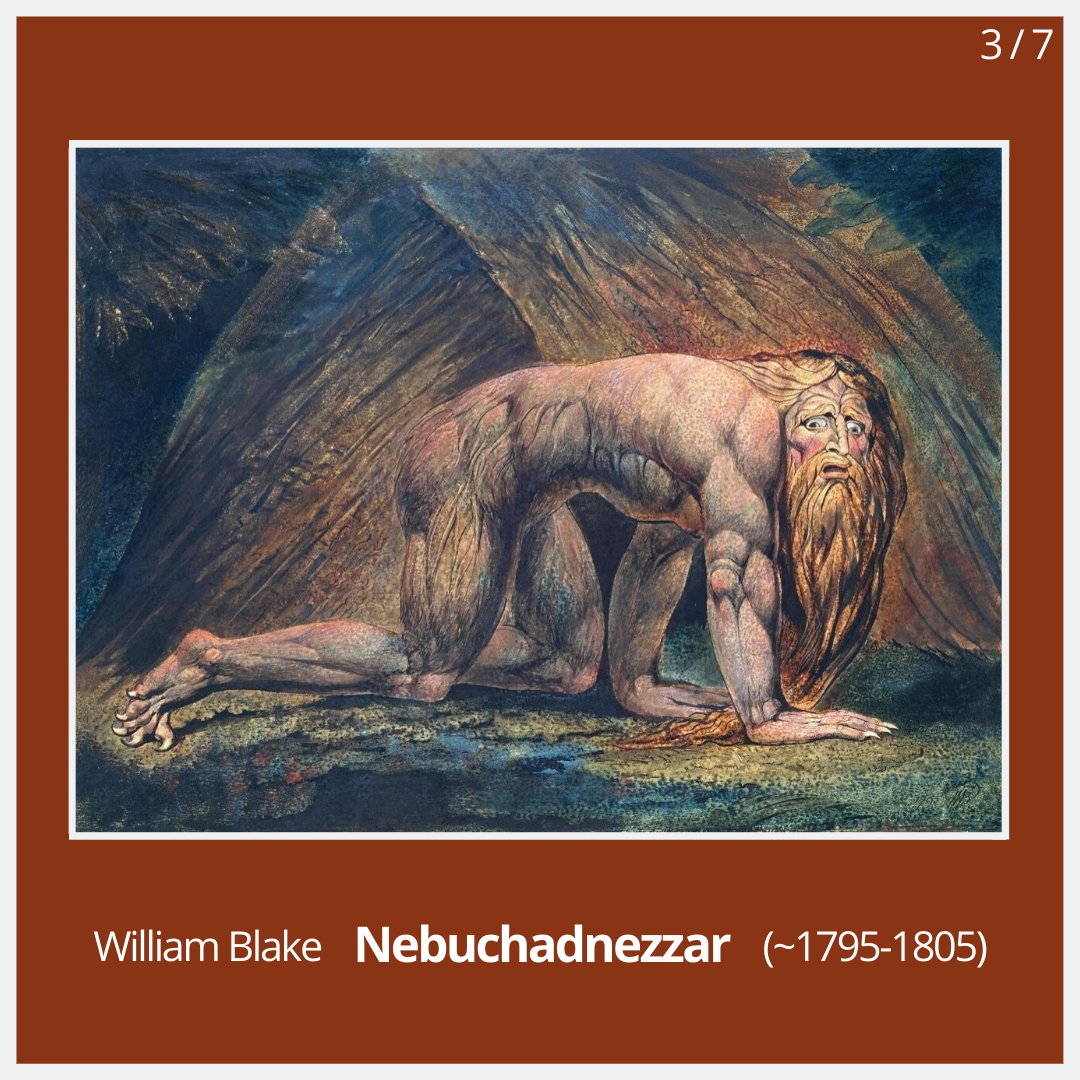

In Giuseppe Verdi’s opera Nabucco (1842), both the anti-hero Nebuchadnezzar and his supposed daughter Abigaille (who is in fact the descendant of Hebrew slaves) are guilty of chutzpah, he for proclaiming himself a god, and she for trying to seize the throne – and both are duly punished. Probably the most vivid image of the punishment of Nebuchadnezzar is the hand-coloured print by William Blake of the king driven to madness, hirsute and on all fours like a beast of the field.

Belshazzar, in some versions Nebuchadnezzar’s son, was also punished for flouting the will of the Lord and mistreating the chosen people. Rembrandt’s Belshazzar’s Feast (National Gallery, London) dates from early in his career and is perhaps the most Baroque and operatic picture he ever painted. It depicts the moment at the height of the feast when the writing appears on the wall, prophesying Belshazzar’s doom. It is the kind of coup de théâtre loved by every Italian opera composer. The three main characters are portrayed with their mouths wide open as though they were singing, and it could be one of those climactic ensembles characteristic of early Verdi. The Baroque style and opera as an art form were born and developed simultaneously. One could say that opera is inherently Baroque and the Baroque style inherently operatic.

In a famous Monty Python sketch, the carter in Constable’s Hay Wain complains to God in a Renaissance painting about the noise coming from the Bruegel room at night. He might equally have complained about this early Rembrandt, which is also a very ‘noisy’ painting.

As we consider our current tragic situation, many will find timely metaphors in these Biblical stories of mankind punished for defying God’s will and abusing the wonderful world that He/She has created for us.

©Patrick Bade

Patrick Bade is an art historian, writer and broadcaster. He studied at UCL and the Courtauld and was senior lecturer at Christies Education for many years. He has worked for the Art Fund, Royal Opera House, National Gallery, V&A. He has published on 19th- and early 20th-century painting and on historical vocal recordings. His latest book is Music Wars: 1937–1945.

www.martinrandall.com/patrick-bade