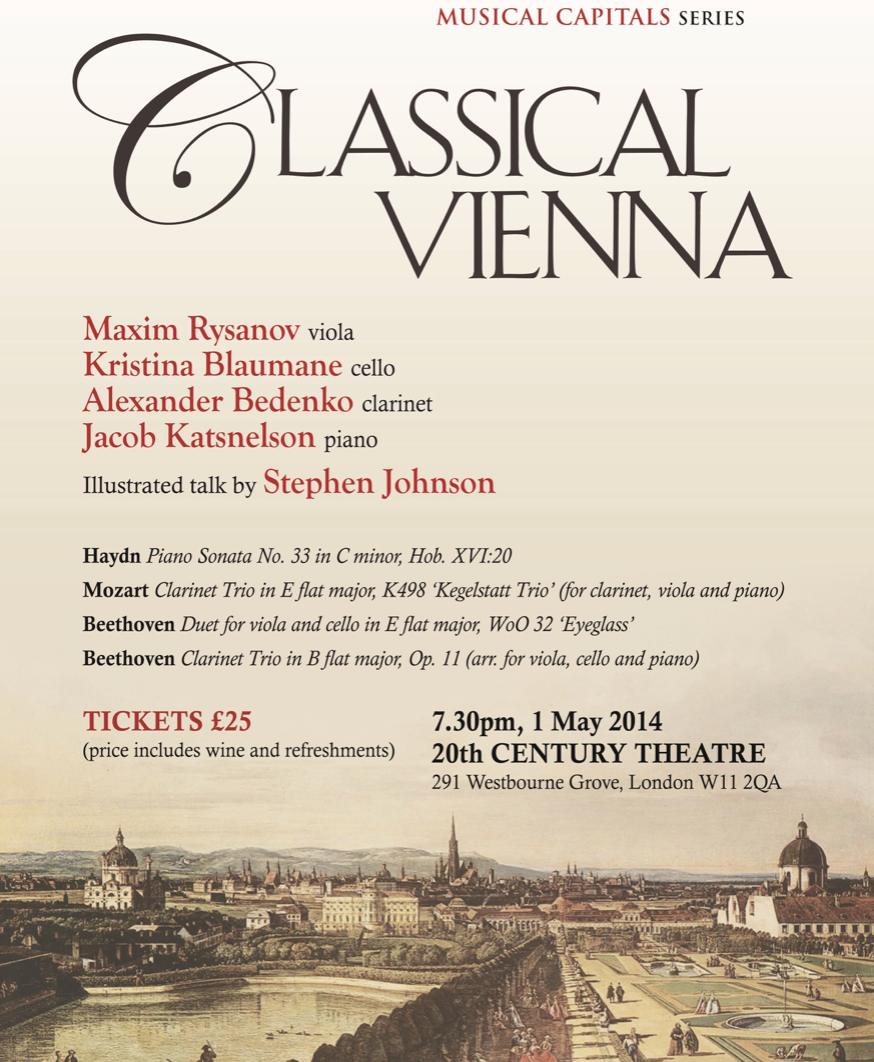

CLASSICAL VIENNA

MAY 1, 2014

20th Century Theatre, London

Maxim Rysanov viola

Kristina Blaumane cello

Alexander Bedenko clarinet

Jacob Katsnelson piano

Illustrated talk by Stephen Johnson

Haydn Piano Sonata No. 33 in C minor, Hob. XVI:20

Mozart Clarinet Trio in E flat major, K498 ‘Kegelstatt Trio’ (for clarinet, viola and piano)

Beethoven Duet for viola and cello in E flat major, WoO 32 ‘Eyeglass’

Beethoven Clarinet Trio in B flat major, Op. 11 (arr. for viola, cello and piano)

Today, Haydn and Mozart are routinely labelled ‘Classical’. But for a brilliant younger contemporary of theirs, the writer, composer and critic E.T.A. Hoffmann, they were ‘Romantics’, and Beethoven was their natural successor. What we now call the Classical Era was an age of ferment and transition. When Beethoven was born in 1770, composers were liveried servants; by the time of his death in 1827, the composer had become an artistic hero, the true heir of the democratic, revolutionary Napoleon. Vienna registered this epochal change in its own paradoxical way. The capital of the centuries-old Holy Roman Empire was a bastion of political and cultural reaction. Yet it was also an international city, to which people flocked from far and wide, bringing with them contrasting cultural attitudes and beliefs. The shock waves of the French Revolution were registered in a variety of ways: secretly in Masonic lodges, and publicly in the subversive comedy of Mozart’s Marriage of Figaro. This was also the so-called Age of Enlightenment, in which intellectuals of many disciplines were challenging the authority of the throne or the pulpit, and arguing that truth could only really be found by independent enquiry, and tested by discussion with similarly independent minds.

The first stirrings of Romanticism, revolutionary thinking, the spirit of courageous enquiry and delight in disputation – all of this can be heard, long before Beethoven’s incendiary ‘Eroica’ Symphony, in the chamber and instrumental music of Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven himself. But the ‘Classical’ label is not simply wrong. This was an age in which new musical forms were being perfected, in which Sturm und Drang was countered by an instinct for balance and elegance of proportion. The paradox of Vienna is also the paradox of its music.